China is strengthening its economic ties with Pakistan and pushing a strategic agenda that outs it into a posture of dominance and power in Asia

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor would provide China with close access to the Indian Ocean, with economic benefits to both China and Pakistan. However, violent separatists in Pakistan are set against the Corridor’s success, and violent separatists in China might see the Corridor as a prime target. China and Pakistan’s ability to provide security for the workers will be key to the success of this geopolitical and economic power play. Though people might desire peace between China and the US, nevertheless China’s actions seem to attempt positioning the nation to contest the US as the dominant world power. The Corridor, coupled with China’s plans to increase its contact with the Middle East and Eurasia, geographically positions China to be an increasingly influential nation that just so happens to be less than best friends with the US. So while China and the US need to find common ground to remain at peace as much as possible, the US also needs to expand its own influence. The US would be wise to do the same with its own allies while pursuing more allies and increase its ability to project power.

Background to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

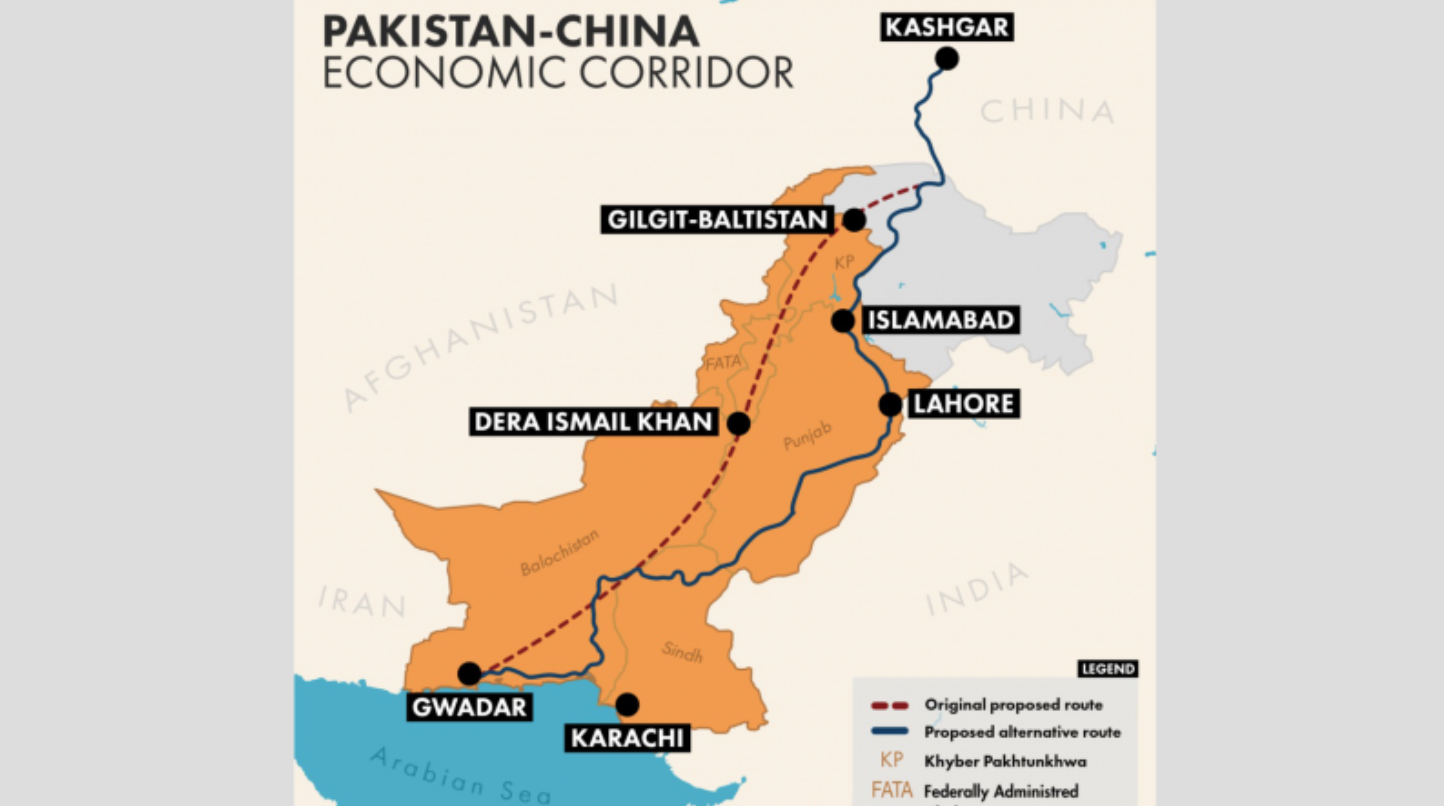

At present, more than 70 percent of China’s trade and energy imports, and 40 percent of its oil, passes through the Indian Ocean and the Malacca Strait..9 However, the Malacca strait is not only full of pirates, but it is also patrolled by the US and Indian navies.9 China fears that, should a conflict arise, the US and its allies could easily break China’s logistical backbone by asserting direct control over the Malacca strait.

As a result of this vulnerability, China is searching for another major trade route and sees one through Pakistan.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is a collection of over 51 agreements and Memorandums of Understandings between the two nations, including physical access to the Indian Ocean through Pakistan.7 Previous Chinese investments were not as large as promised.2 Indeed, in 2009, China – in response to the deteriorating security situation in Baluchistan (southwestern Pakistan), including Baluch separatist violence against Chinese engineers – decided to not build a multibillion-dollar refinery in the Pakistani deep sea port of Gwadar.6 Gwadar is in Baluchistan and is currently operated by the Chinese state-owned Overseas Port Holding Company.7 However, China now seems quite keen on success. Pakistan is as well: Pakistani officials are adamant that nothing will keep success from the Corridor.2

Elements of the Corridor

The Corridor is China’s attempt to advance its geopolitical power and security, done in a way to also benefit Pakistan’s economic and security situation. Pakistan already sees China as an important neighbor. Indeed, China is Pakistan’s largest arms supplier and trading partner.1 By 2030, China plans to invest 46 billion dollars into Pakistan (the last US economic package to Pakistan spanned 2009 to 2014 and amounted to 7.5 billion dollars8).2 The projects include a 3000km railroad, road, and oil pipeline from Kashgar, China to Gwadar, Pakistan.7 Kashgar is a trading hub in western China, and China is hoping the Corridor will allow oil and gas from the Persian Gulf to be piped from the port and into China.2 In addition, China would have access to a much shorter route for exporting goods, at least as compared to the Malacca Strait.2 China would also have a larger geopolitical influence in the Arabian Gulf region.9

Other projects include a fiber-optic cable from China to a city next to Islamabad, the Gwadar International Airport, nine coal power plants, five wind farms, three hydroelectric dams, and one solar park.6; 9; 10 Each year Pakistan loses 4 to 6 percent of its GDP to poor infrastructure, at least in part because the poor water infrastructure limits the country’s agricultural potential.9, 12 The 18 energy projects China is planning would offset the electricity shortage in Pakistan, and the Corridor as a whole has the chance to provide a positive 2 percent growth to Pakistan’s GDP.10; 9

The Corridor would not only provide China an enhanced connection to the West, but it might also manage to keep Pakistan from becoming a poorly-functioning state. 5; 8 Finally, of extreme importance, China would be a two-ocean power.8

Threats to the Corridor

The most serious threat to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is the violence in Baluchistan, the Pakistani district that contains Gwadar. The separatist insurgency in Baluchistan began a decade ago and remains a threat. In January 2015, Baluch separatists attacked Pakistan’s electric grid and 80 percent of Pakistan lost power.2 On 29 May, Baluch gunmen slaughtered all passengers on a bus that they considered not native to Baluchistan.2This episode would demonstrate the potential threat posed to Chinese workers in Baluchistan, only the threat is real: In March of 2015, Baluch separatists attacked Chinese workers related to a mining project.2 In addition, the separatists have no interest in the development of Gwadar port until Baluchistan is independent.2 A Baluch leader referred to the Chinese when he declared, “We have not invited them.”6 He went on to say that the Baluchs were forced to “defend our land.”6 Baluch separatists want to be independent before the port develops.6Pakistan has promised to commit a 10,000 man security force to protect Chinese workers.2 However, so far Pakistan’s actions against the Baluchistan separatists, which the Human Rights Watch has called “an abusive free-for-all” of disappearances and executions, have only worsened the situation.2; 13

Other security threats loom at the Corridor’s upper end: In China’s Uyghur Autonomous Region, the security situation is deteriorating rapidly.6 The Uyghur’s could see striking the corridor as an effective assault against China. Furthermore, part of the Corridor passes through an area of land India claims to be its own, namely Kashmir. Indian analysts see the Corridor as a pincer strategy to allow China and Pakistan to trap India, and China’s growing military presence does little to assuage India’s fears.6

China seems to assume that development brings peace.6 A Pakistani development expert stated, “One should keep in mind that development does not bring peace, rather it is peace that brings development.”6 The end result of the unrest and China’s approach could lead to more unrest in already disturbed and violent regions.6Fortunately, China already hopes that the Corridor will provide Pakistan with a long-term incentive for stopping terrorism.10

Future of the CPEC

China’s end goal is to develop a connected network between at least five regions: Russia (the primary bridge between Asia and Europe), the Central Asian “stans,” Southwest Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe – as well as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.11 China will build a pipeline from Iran to Pakistan to help solve Pakistan’s energy shortage.4 China has also called for cooperation with Iran on high-speed railways and telecommunications.3 China would also have access to the copper and oil of Afghanistan.8 Other target nations include Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Belarus, Moldova, and – potentially if stable – Ukraine.11 China has also reached out to Sri Lanka and India, but China’s focus remains on Pakistan.5

China seems to be positioning itself closer to Eurasia, which Mackinder’s geographic theory names as key to world power. At the same time, China’s focus on Gwadar seems to indicate a move toward Mahan’s theory that sea power is the key to controlling the world, including Eurasia. China seems to be pulling two apparently opposing geographic theories into one strategy, positioning itself to be an ever more important world force. If China succeeds, then a nation – with a strange and tenuous relationship with the US – quite possibly would have achieved a milestone in replacing the US as the dominant world power.

Conclusions

China’s efforts will likely displace the US as Pakistan’s core international patron.8 The US needs to choose the battles worth fighting. How important is Pakistan to the US? If China’s efforts bring stabilization, though the road will likely be quite rough, is that worth letting Pakistan slide to China – especially since Pakistan already is heading that direction? Perhaps. The US has failed to pacify the violence in Pakistan, and China’s actions overshadow whatever Pakistan-US ties that currently exist. In some sense, Pakistan is a failed attempt at US policing.

Asia is becoming a complex mess of alliances, the same situation that in Europe caused one assassination to turn into the Great War. China is posturing itself to be ready if conflict arises, and the US needs to do the same. The US would do well to focus resources on strengthening trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, instead of pouring a relatively inconsequential sum of money into Pakistan. In addition, the US should increase its naval capabilities and capacities, perhaps by building smaller, more versatile aircraft carriers, to counter China’s dual geographic strategy. Aircraft carriers are the ultimate method of power projection. Building more would allow the US to better take advantage of Mahan’s sea power theory to neutralize China’s apparent embrace of Mahan’s and Mackinder’s theories and resulting world influence. ■

- Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, “China’s pro-Pakistan state media blitz may be more about convincing its own people,” Foreign Policy, 22 April 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/04/22/china-pakistan-relations-trade-deal-friendship/.

- The Economist, “Dark Corridor,” The Economist, 6 June 2015, http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21653657-conflict-balochistan-must-be-resolved-trade-corridor-between-pakistan-and-china-bring.

- Teddy Ng, “Iran backs pipeline to China under ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative: Ambassador,” South China Morning Post, 27 April 2015, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/1774422/iran-wants-help-energy-pipeline-expansion-part-chinas.

- Saeed Shah, “China to Build Pipeline From Iran to Pakistan,” The Wall Street Journal, 9 April 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-to-build-pipeline-from-iran-to-pakistan-1428515277.

- Shannon Tiezzi, “China, Pakistan Flesh Out New ‘Economic Corridor’,” The Diplomat, 20 February 2014, http://thediplomat.com/2014/02/china-pakistan-flesh-out-new-economic-corridor/.

- Gordon G. Chang, “China’s Big Plans for Pakistan,” The National Interest, 10 December 2014, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/chinas-big-plans-pakistan-11827.

- Hussain Nadim, “Game Changer: China’s Massive Economic March into Pakistan,” The National Interest, 23 April 2015, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/game-changer-chinas-massive-economic-march-pakistan-12711.

- Claude Rakisits, “How China Could Become a Two-Ocean Power (Thanks to Pakistan),” The National Interest, 12 June 2015, http://www.nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/how-china-could-become-two-ocean-power-thanks-pakistan-13101.

- Mahwish Chowdhary, “China’s Billion-Dollar Gateway To The Subcontinent: Pakistan May Be Opening A Door It Cannot Close,” Forbes, 25 August 2015, http://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2015/08/25/china-looks-to-pakistan-to-expand-its-influence-in-asia/.

- Tim Craig and Simon Denyer, “From the mountains to the sea: A Chinese vision, a Pakistani corridor,” The Washington Post, 23 October 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/from-the-mountains-to-the-sea-a-chinese-vision-a-pakistani-corridor/2015/10/23/4e1b6d30-2a42-11e5-a5ea-cf74396e59ec_story.html.

- Pepe Escobar, “Can China and Russia Squeeze Washington out of Eurasia,” The Nation, 6 October 2014, http://www.thenation.com/article/can-china-and-and-russia-squeeze-washington-out-eurasia/.

- APP, “Pakistan losing water resources due to poor infrastructure: experts,” Pakistan Today, 22 March 2013, http://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2013/03/22/national/pakistan-losing-water-resources-due-to-poor-infrastructure-experts/.

- Palash Ghosh, “Balochistan: Pakistan’s ‘Dirty War’ In Its Poorest, Most Lawless, But Resource-Rich Province,” IB Times, 14 September 2013, http://www.ibtimes.com/balochistan-pakistans-dirty-war-its-poorest-most-lawless-resource-rich-province-1405620.

Fall 2015

Volume 17, Issue 8

30 November